Verse 33

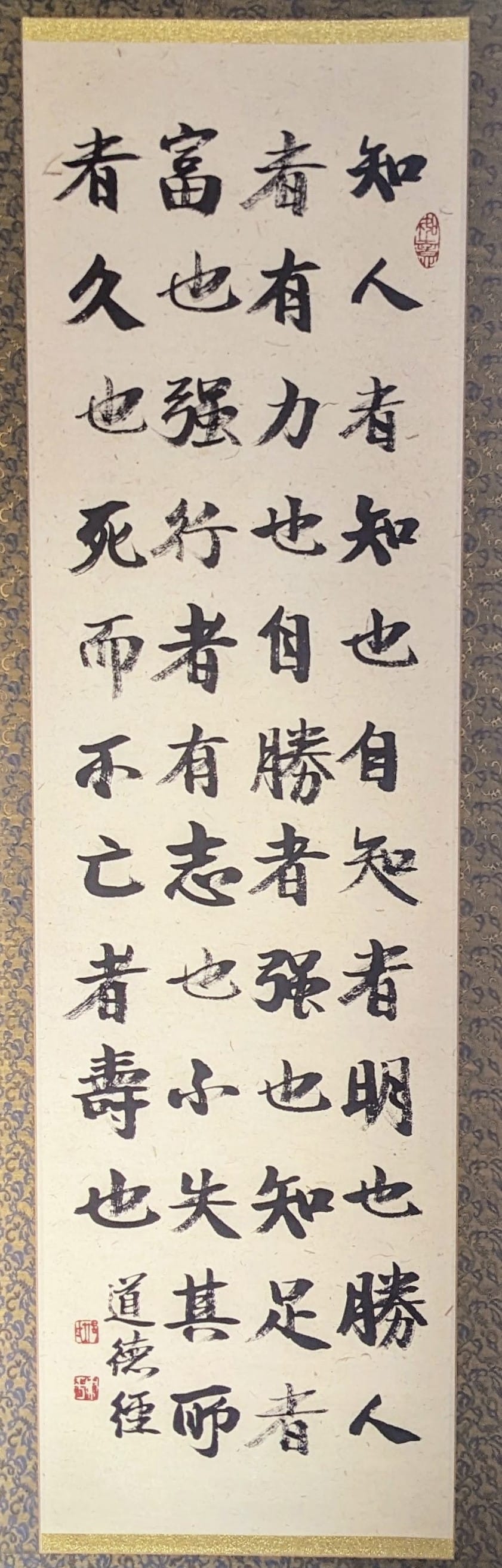

A little supplementary post because once, over a decade ago, I already translated verse 33 of the Tao Te Ching, but it's still important to me (it runs in calligraphy on a scroll on the wall beside me still!), so I'd like to record it anew here!

I have a few English translations of the verse, and a book analysing the characters used in the ancient Chinese text, with explanations about their shades of meaning and how they go together. I translated my favourite English version into Esperanto, and then tweaked it using the explanations of the Chinese characters, because my own Chinese knowledge remains as awful as it ever was, and I know even less about more ancient forms of it!

konante aliajn, oni inteligentas.

konante sin, oni saĝas.

venkante aliajn, oni fortas.

venkante sin, oni ĉiopovas.

forte alpaŝante vivon, oni ja akiras ion.

kontentante pri sia vivo, oni ja akiras ĉion.

dediĉante sin al sia vivejo, oni vivas longe.

mortante tamen ne forgesote, oni ja vivas eterne.

Making quite a literal English translation of this, you get:

in knowing others, one is intelligent.

in knowing oneself, one is wise.

in conquering others, one is strong.

in conquering oneself, one is all-powerful.

approaching life forcefully, one surely gets something.

in being content in one’s life, one surely gets everything.

in being dedicated to one’s place in life, one lives long.

in dying but not being forgotten, one surely lives forever.

In my opinion, the English version in this style looks stunted and without flow; it needs more umpf to make it sound nice. This is the style that my favourite translation goes for:

one who knows others is intelligent

one who knows oneself is enlightened

And even here, most lines have to be prefixed with “one who”. It kinda helps it flow, and sometimes repetition is part of the rhythm, but I'm greatly preferring the Esperanto rendering.

From what I can tell, my Esperanto version is also much closer to the ordering and use of the Chinese characters than this English version, especially given that the Esperanto words mostly map one-to-one with the characters, which I found to be a beautiful coincidence when I first discovered this! For example, that first line is:

知人者智

konante aliajn, oni inteligentas

Being able to express those qualities as verbs like inteligentas instead of estas inteligenta brings such concision, and the slight feeling that they are actions to be lived, rather than qualities that you have or don't.

I particularly enjoyed discovering terms like:

ĉiopova

all-powerful, from ĉio "everything" + pova "able", able to do everything

alpaŝi

to approach, from paŝi "to step" + al "to, toward"

And, as originally suggested by a reader of the ancient blog, Vaughn:

vivejo

one's place (in life), from vivo "life" + ejo "place"

I think it improved on just a simple word like loko "location" or ejo "place", because it more immediately shows that it's not just a physical place we're talking about, and it brings a little style matching viv- the subsequent oni vivas longe.

Back then, I was quite unsure about part of the last line:

ne forgesote

literally: not going to be forgotten, from the future passive adverbial participle (phew!) form of forgesi "to forget".

But these days I'd argue its logic and simple beauty.

On the left, the scroll hanging on the wall beside me featuring verse 33, and the words "Tao Te Ching" at the lower left. On the right, an image generated using a prompt to DALL·E 3